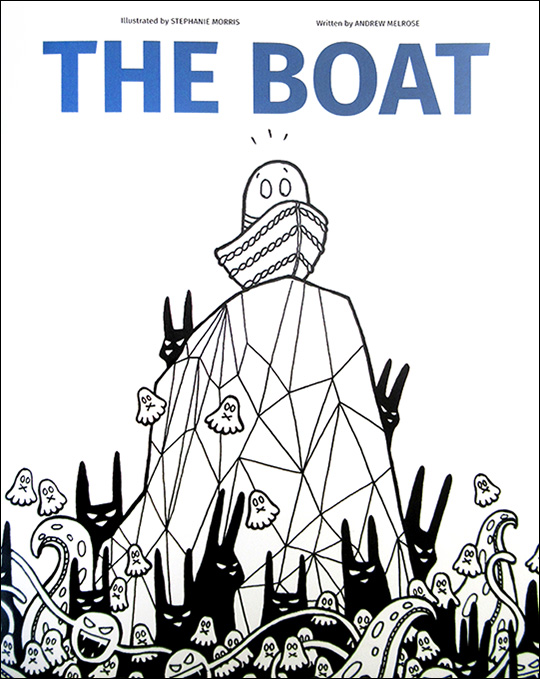

I am currently involved in the ongoing making of a project called The boat (Melrose and Morris 2017) supported by the University of Winchester (UK) and the Arts Council England.

It’s a long term and continuing venture, designed to open up a dialogue with children on the fraught subject of ‘forced migration’. The critical and school supporting material can be accessed in electronic form via the website, http://the-immigration-boat-story.com/ and a copy of the book can be seen here, https://vimeo.com/245075528. There are also three essays in the journal, Writing in Education (vol 67, 68 and 69) on the research with children and schools, which will be followed up on as the project proceeds (with 120,000 school children in the UK).

In this paper I would like to highlight some of the critical issues I have encountered in creating the project. To some, it looks like a small picture book illustrating a 280-word poem for children. Nevertheless, the critical rationale behind it investigates a much wider engagement with the role of the writer/poet in the discourse of protest. As such there is a strong critical and creative rationale behind its creation – and some of the ideas in the research came into focus when I was confronted by a journalistic piece by Khaled Hosseini. In an article entitled, ‘Refugees are still dying. How do we get over our news fatigue?’ (2018a) he asks, ‘How can we reconnect to the people risking their lives for a better life’ before going on to state about the drowning of a three-year-old Syrian forced migrant or refugee that, since Alan Kurdi’s death, public outrage has given way to fatigue. This is something that concerned me too. And it suggests an important question: beyond engaging with the stories of forced migrants, how can a writer who hasn’t had the experience inhabit the story of forced migration? What follows is what I uncovered.

Hearing their stories… listening with compassion

Writing a story on forced migration was always going to be a challenge. Both the illustrator, Stephanie Morris, and I wrestled with the idea that we had no entitlement to do so. In some ways, it felt a form of cultural appropriation even to be writing on the topic. Nevertheless, there does seem to be an underlying and ongoing need which isn’t being addressed. Hosseini agrees and goes some way to addressing it in his own book, Sea prayer (2018b). He takes the tragic story of Alan Kurdi (who died off the coast of Dalaman in Turkey) as inspiration to bring out a poetic response to the idea that compassion for migrants has faded. He was responding to a picture that had been building for some time. In 2016, Patrick Kingsley reported:

Sitting in a refugee camp in northern Greece, Mohammad Mohammad, a Syrian taxi driver, holds up a picture of three-year-old Alan Kurdi. It is nearly a year since the same photograph of the dead toddler sparked a wave of outrage across Europe, and heightened calls for the west to do more for refugees. Twelve months later, Mohammad uses it to highlight how little has changed … Alan may have died at sea, he says, ‘but really there is no difference between him and the thousands of children now dying [metaphorically] here in Greece’ … Tens of thousands have been stranded in squalid conditions in Greece since March, when Balkan leaders shut their borders. ‘It is,’ says Mohammad, ‘a human disaster.’ (2016: n.p.)

Hosseini, writing two years later, came to the same conclusion. He writes:

Where is the outrage, one wonders …? But over a heartrending, and often heartening, week spent listening to refugees in Lebanon, then Sicily, I stumble time and again into the same thought: I wish the world could hear what I am hearing … Each story I hear from a refugee helps me feel, bone-deep, my immutable connection to its teller as a fellow human. (2018a: n.p.)

I was struck by his need to respond to the ‘bone-deep’ connection with the stories he heard. Especially when he tells us, ‘I see myself, the people I would give my life for, in every tale I am told …’ It’s a heart-rending piece, full of pathos and compassion for the plight of those still dying while looking for a better life. And indeed, so too is his Sea prayer. What marks out Husseini’s article and book is both the compassion and his reflection of the ‘bone-deep … immutable connection’. But these are issues which need to be addressed carefully.

Firstly, the ‘fellow human’ notion is not one that everyone shares and is currently drowning in the rhetoric of opposition. Hosseini asks, ‘Where is the outrage …’ but, of course, responses to refugees are caught up in a wider political ‘forced migrant’ discourse – one of the inevitable consequences of contemporary government policies and intervention, such as the Australian internment of forced migrants on Manus and Nauru islands; or the British Prime Minister, Theresa May telling the country she wants the UK to be hostile country to them; or various countries across the world identifying migrants as a threat to national security and wellbeing. This is corrosive. And it is easy to see how this narrative of opposition survives through the dominant discourse of political power. It is electorally expedient, home politics (wherever our home is) that has come to rely on ‘othering’ the foreign presence or suggesting the threat of imminent ‘invasion’ (the former UK Prime Minister, David Cameron, referred to migrants crossing the Mediterranean as a ‘swarm’, like locusts). Slavoj Žižek addresses this idea, even as he exposes the intolerance of others:

Today’s liberal tolerances towards others, the respect of otherness and openness towards it, is counterpointed by an obsessive fear of harassment. In short the Other is just fine, but only insofar as his presence is not intrusive ... What increasingly emerges as the central human right in late-capitalist society is the right not to be harassed, which is the right to remain at a safe distance from others. (2008: 35)

However, I have a profound problem in aligning Žižek’s quotation with the ‘forced migrant’ situation, especially the idea of forced migrants as ‘others’. While Žižek goes on to suggest they are like Frankenstein’s monster (we know he deserves our help but we close the door), it’s too easy to say it’s a simple case of them and us, or theirs and ours.

The ‘forced migrant’ is not ‘other’ to our ‘selves’. While travelling, they occupy a radically different social space, one which is contingent and genuinely temporary. But the forced migrant is a temporary identity under erasure. They truly are in the process of becoming a migrant no more – once their limited space of habitation is rendered obsolete. This brings us back to Hosseini’s notion of compassion fatigue, then, and the idea that we should be reconnecting with their stories. He says,

Stories are the best antidote to the dehumanisation caused by numbers. They restore our empathy … The story of Khadija, for instance, a 31-year-old Afghan mother I meet in a small town in Sicily, where she has lived for the past month … Listening to her, I marvel at the despair it would take me to put the people I cherish most on a rickety boat to cross a vast sea, knowing how thousands have perished before me attempting the same journey. I picture the pitch-black moonless nights, waves high as walls all around, sea water lashing at my skin, my mother praying, my children terrified, their lives in the hands of smugglers whose business model thrives on human misery. (2018a: n.p.)

His Sea Prayer was written in response to this kind of story, and indeed it was written to appeal to someone like me. I too feel the need for a more kind-hearted approach to the entire debate. But in writing a narrative to stir our compassion, Hosseini, in his journalistic companion piece, also (probably unintentionally) reveals how difficult it is to address the problem of disconnection he is presenting. The result is that despite the care he takes, the pair do not match up and compassion itself is the problem.

Compassion has its place in the discourse surrounding forced migration issues. Of course it does, if for no other reason than to keep the dialogue about such matters alive in the face of political opposition. Refugee charities depend on it, refugees themselves need it. Nevertheless, this evades a simple fact, which is that forced migration is a story of humanity in the modern world, involving people (just like us) who should (just like us) be the subject of human rights rather than simply the object of our compassion. Furthermore, this is not just their concern, these are not just ‘their stories’. What needs to be acknowledged is that the story of forced migration is our story too. We cannot outsource the morality of a forced migration discourse, by defining the migrants as ‘other’ or calling it ‘their story’ just because (this time around) forced migration happens to others and not us. The reasoning is simple enough: this story belongs to us all. Human rights are about the rights of every individual, not just the compassionate noise we make on behalf of ‘others’.

Thus, the job of a writer concerned with these issues risks being problematised by assumptions. Compassion isn’t enough for such a writer – he or she has a pivotal role in finding ways of exposing the truth of the circumstances being addressed. The reason is simple. Taking on the Žižek’s idea of the ‘other’, what needs to be exposed is that ‘forced migrants’ as a hauntological presence are monstered not monsters. Considered as outsiders, the ghost of all our pasts, they are so often considered as mythical non-beings coming to terrorise us, instead of people caught up in a human tragedy which we are a part of – for it is our tragedy too. Understanding this position is important. If we, as writers, are to inhabit the story of forced migration, we accept it is our story too. This then, brings me to The boat project.

The issue of ‘forced migration’ is one of the great tragedies of our present day. But as long as men and women and children have been on earth, they have taken to the sea for safety and in search of a better life. We could go a long way back on this because archaeologists have revealed many millennia of of sea travel. And the Iliad and the Odyssey also immediately come to mind. Exodus 1:1-2:10 reminds us that to save her baby from being thrown into the River Nile, one mother laid this baby in a basket and set him on the river among the reeds. She hoped an Egyptian woman would find him and raise him. The rest of the story of Moses is fairly well known but he was a ‘forced migrant’. Thus, while the stories of ‘forced migration’, hazardous trips across the Mediterranean, carry tragedy with them, what can be invested in a simple story of a journey has the capacity to carry a much deeper meaning.

The boat

© Stephanie Morris (2017)

Our plan wasn’t to write a cute story about a baby being put in a basket, but a story about adversity and survival. In turn, we wanted to create a story which invites others to encounter the real world in a different way. The reasoning was: if we can introduce children to the idea of a story with real, potent meaning early on in their lives then surely their understanding of the world as they grow into adults will be enriched. This is a conviction built on the premise that writing for children isn’t about writing little stories but big stories told short.

As Dominique Hecq (2018: 196) reminds us, ’Inhabitation’ is a lovely word. Like Freud’s ‘Unheimlich’ (strangely familiar) it evokes a doubling: that which I inhabit and that which inhabits me.’ From this we can begin to assemble an idea of what ‘inhabiting’ the ‘forced migration’ story means as belonging to us all. And as Philip Pullman (2018: 123) suggests, literature should have no borders, ‘stories shouldn’t need passports’ to survive. What is important is the layers of story they tell. This is what we (the artist Stephanie Morris and I) tried to do with The boat. Our intention was to make it an inclusive story, one which includes the reader in the narrative. But also one which brings the reader to a story they had previously considered someone else’s – or at least hadn’t considered their own. Though how to do this remains a challenge, especially considering that we were writing for children.

Kevin Brophy (1994) points out that originality in storytelling is dependent on shared reference points which enable meaning to exist. In this regard, we have long since evolved as a species to know that writing, literature, poetry, song and other artworks for children exist to offer vicarious experience. This is a healthy way of introducing difficult topics to children, so they may assimilate the shared reference points. They add what they don’t know to that which they do as a means of gaining experience. Furthermore, as Goswami confirms,

It is now recognized that children think and reason in the same ways as adults from early childhood … Cognitive development is experience-dependent, and older children [and adults] have [just] had more experiences than younger children. (2008: 1-2)

In the initial ideas on the story Stephanie Morris and I developed, it begins with a mother putting a baby (Moses-like) in a basket on a river. The basket ends up on a refugee boat and the story ends with the boat trying to land in a country that doesn’t want it. The story implies that its main characters are ‘forced migrants’ without confirming this. They are indicated to be simply men, women and children looking for a better life; highlighting their plight and problems for a specific child-centred audience. And the idea of joining a Moses story idea to a child on a Dalaman beach (as echoed in the Hosseini story) resonates the centuries old human story of people looking for a better life.

Introducing such difficult subjects to children is not as problematic as it seems. What the story allows them to do is, ‘discover that they are still alive and outside the story’ (Warner 1998: 6). And, as Bruno Bettelheim has written, ‘only hope for the future can sustain us in the adversities we unavoidable encounter.’ (Bettelheim, 1976: 4). What the story can deliver is an understanding of the significant danger and precarity faced by forced migrants. Nevertheless, this is not a manifesto or a ‘didactic’ story, but a way of allowing children to engage in the various positive and negative issues that helps them to find meaning in life and the world. The boat is set up to reveal people with loves, fears and desires who are looking for a better life.

In the The boat the text begins:

A mother put her basket in a basket,

then put the basket into the river,

singing, ‘hush little baby, don’t you cry…’

and the hushed little baby stayed quiet…

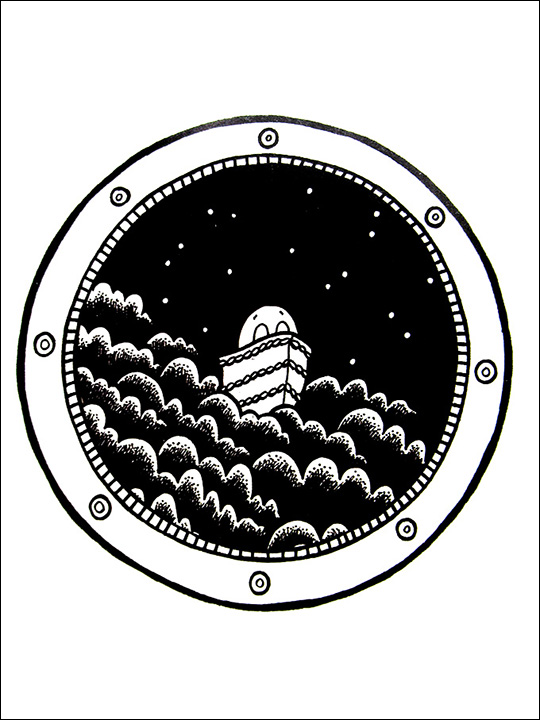

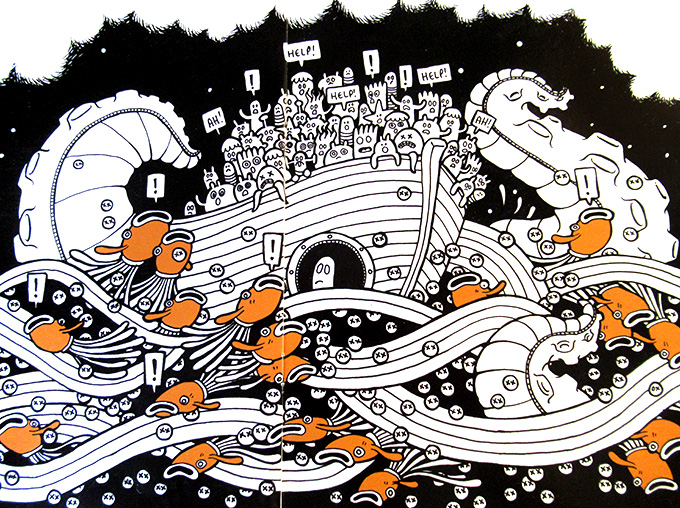

There was no intention to re-write the story of Moses but the trace of Moses as a ‘forced migrant’ is visible. So, too, is the idea of a shared reference point (many adults have applauded their own recognition of this fact in readings I have conducted). The story itself is a predictable enough one in storytelling terms and the shipmates encounter a storm on the way:

© Stephanie Morris (2017)

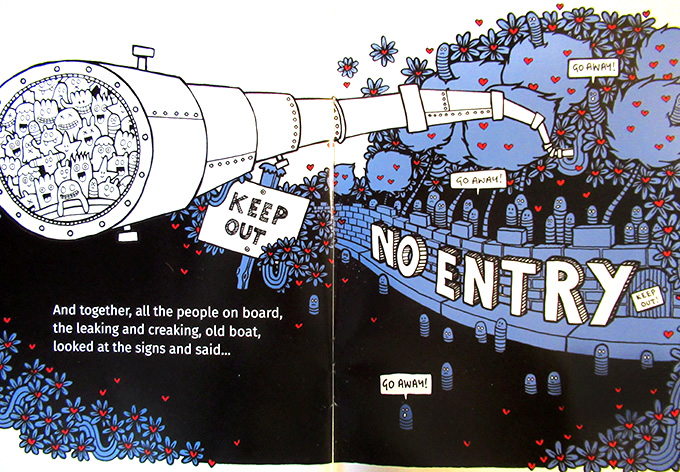

They arrive at the place where they think there is a better life, only to be confronted with ‘go away signs.’

© Stephanie Morris (2017)

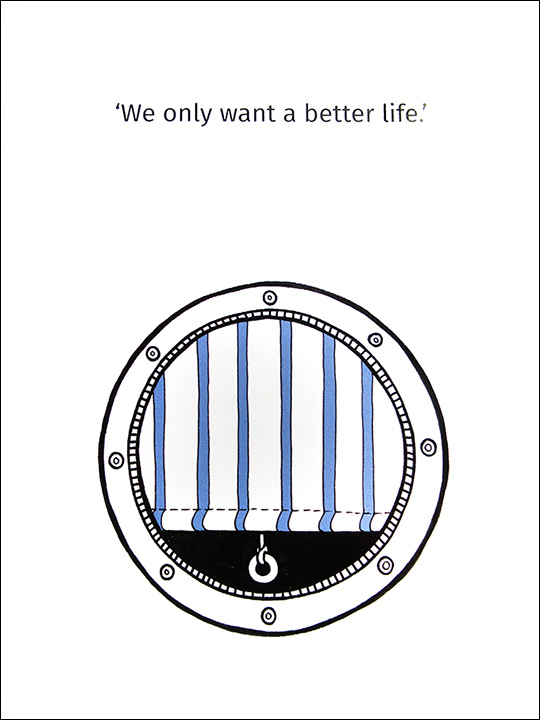

The last page reads, ‘We only want a better life’.

© Stephanie Morris (2017)

We only want a better life. It is a timeless hope and surely a human right. What has continually been raised, however, (in a study conducted with schools) is the question of what happens next? And this is the key to readers’ inhabitation of the story because our response is, ‘What do you think happens next?’ or even, ‘What do you think should happen next?’ In other words, the story asks schoolchildren to try and locate themselves in the narrative rather than to read it as a story belonging to others. Neither I nor over 99 per cent of readers know what it is like to be a forced migrant, but that is not the point. This isn’t an attempt to push a compassion button but to ask questions of our role in the story. If I don’t want migrants in my back yard, or next door to me, where do they go? What does happen next? I am already inhabiting the story because everyone faces connected issues.

Just as the story of Moses in the Old Testament isn’t merely a story about a mother’s concern about a small boy, the child in The Boat is a representation of a person seeking their human right to survive. Giving this story to children was deliberate, too, because they are the future in this debate and, like the ‘forced migrant’, their label (as children) is temporary. A child is an identity under erasure; childhood is temporary. The child only has a few years before he or she is camouflaged as ‘one of us’ and marked out by their experience of life.

This is where writers come in. A story or poem is a meeting place where vicarious experiences can be negotiated and located. What is actually taking place in the cultural process of storytelling is a way of encouraging children to learn how to articulate their own stories while assimilating a story that is new to them. The boat project elaborates on the ways of representing forced migration while demonstrating how a very specific child-centred audience might be introduced to a complex human story.

Reordering the order

If art is about truth, about touching the depths of human experience, then the art of writing has a deeply-felt responsibility to rub against the very boundaries of language and truth in the face of opposition. It may drift between what is real and what is imaginary, between what is real and what is make-believe, and as Ali Smith says:

Fiction and lies are the opposite of each other. Lies go out of the way to distort and turn you away from the truth. But fiction is one of our ways of telling the truth. (2018: n.p.)

We can couple this idea to Simon Critchley’s when he explains ‘the twofold task of poetry’:

We find order in things. This is not an order that is given, but one that we give. Poetry reorders the order that we find in things. It gives us back things exactly as they are, but beyond us, ‘a tune beyond us, yet ourselves’ … Poetry is the enchantment of the world, the incantation or reality under the spell of imagination, a world spelled out through words. (2005: 57)

Writing on difficult issues is about taking the story and stretching the promise of engagement it represents, deepening the thinking contained within it and making it ‘more intense and profound’ (2005: 57). The writer gives life to the story, which is, in any case, about life itself. This ‘way of telling the truth’ (as Smith implies) is the bequest of artists, of writers, of poets. And they are in a good place to bring us this. Nigel McLoughlin observes:

The process of writing poetry … is an interpretive process, whereby the poet may engage with their experiences and make meaning from them in order to transform them into material for verbal art. Such meanings can be constructed and modified through the process of writing. Writing poetry (and other forms of creative writing) may be viewed as an investigative process that is capable of generating new knowledge not only in relation to poetics and aesthetics but also in relation to human experience through the process of ‘reaching out into’ those experiences in order to understand them. (2013: 48; my emphasis)

Indeed, as Monica Carroll and Jen Webb have written:

… though poets may be citizens of a minor culture, for the most part they assert a deeply felt connection to their geographic or national topos, and describe themselves as phenomenologically connected to the world, and their societies. They may visit the between-space, and operate professionally in the non-place, but they don’t live there … The space they occupy is ‘other’ to the norm. (2018: 53-54)

Poets are ‘“other” to the norm’ in the way that McLoughlin describes, that is clear, but the lie that the ‘forced migrant’ is another ‘other’ is designed to subjugate a truth. As we have seen, the story or the poem may be a (sometimes counter-intuitive) way of exposing this falsehood. And a big falsehood is the idea that the stories of ‘forced migrants’ are merely ‘their stories’. We are all very much part of this discourse. I return, then, to this idea that their story is our story. We shouldn’t be thinking about how ‘we reconnect’ as Hosseini asks, but how we ‘inhabit’ the story. In acknowledging forced migrants are actually subject to the same human rights as ourselves, rather than simply being objects of our compassion, we can begin to meet the challenge of understanding their situation better – in our own terms as well as in ‘their’ terms. This is about imaginatively re-inhabiting our shared story and giving it meaning for everyone.

Bettelheim, Bruno 1976 The uses of enchantment: The meaning and importance of fairy tales,New York, Knopf

Brophy, Kevin 1994 Creativity: Psychoanalysis, surrealism and creative writing, Melbourne, Melbourne University Press

Carroll, Monica and Webb, Jen 2018 Creativity in context: How to make a poet, Pragmatics of Art 3, Canberra, Recent Works Press

Critchley, Simon 2005 Things merely are, Abingdon, Routledge

Hosseini, Khaled 2018a ‘Refugees are still dying. How do we get over our news fatigue?’ The Guardian, at

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/aug/17/khaled-hosseini-refugees-migrants-stories(accessed 18 August 2018)

Hosseini, Khaled 2018b Sea prayer, London, Bloomsbury

Goswami, U 2008 Byron review on the impact of new technologies on children: A research literature review: child development, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

Hecq, Dominique 2019 Inhabitation: Creative writing with critical theory, Canterbury, Gylphi

Kingsley, Patrick 2016 ‘The death of Alan Kurdi: One year on, compassion towards refugees fades’, at

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/sep/01/alan-kurdi-death-one-year-on-compassion-towards-refugees-fades(accessed 20 April 2019)

McLoughlin, Nigel 2013 ‘Writing Poetry’, in Harper, Graeme ed, A companion to creative writing,Chichester, John Miley and Sons

Melrose, Andrew and Stephanie Morris 2017 The boat, at

http://the-immigration-boat-story.com/

Pullman, Phillip 2018 Daemon voices, Oxford, David Fickling Books

Smith, Ali 2018 ‘Fiction is a way of telling the truth’, at

https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2018/aug/21/fiction-not-lies-is-a-way-of-telling-the-truth-ali-smith-in-edinburgh: accessed 21/08/18

Warner, Marina 1998 No go the bogeyman: Scaring, lulling and making mock, London, Vintage

Žižek, Slavoj 2008 Violence,London, Profile Books