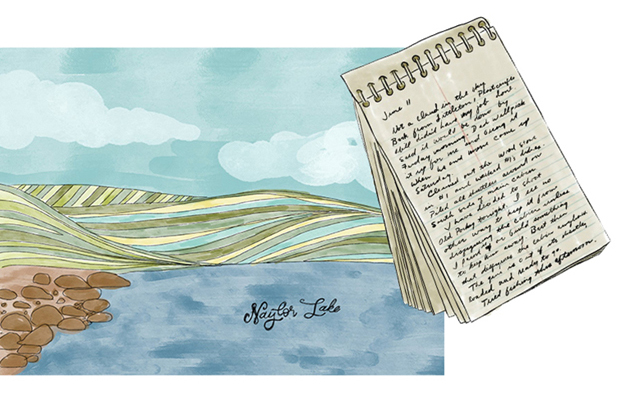

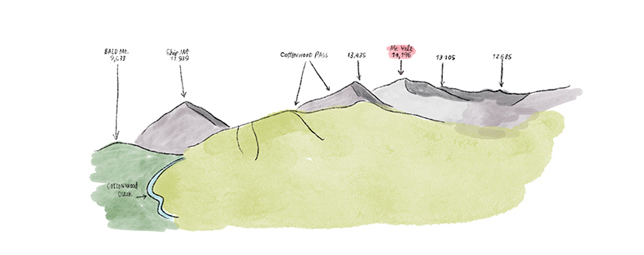

The first mountain I summitted, Square Top, towered 1,994 feet above Naylor lake, a private fishing lake where my father was a caretaker in his 20s. It was the first time I’d ever spent any real, extended time in the alpine.

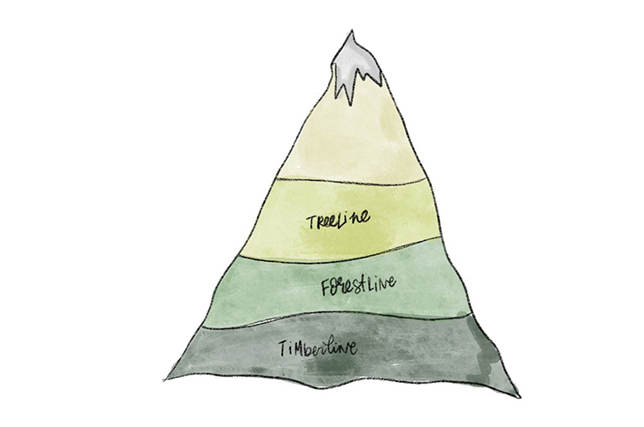

In Colorado, the timberline starts anywhere from 11,000 to 12,000 feet and it’s at this point that the vegetation changes.

Alpine willows bordered the single track trail leading to Square Top Lakes. Melting snow carved small creeks, weaving around branches and granite. Once Anthony, my boyfriend and I arrived at the lakes, the vegetation changed again into windswept tundra, speckled with stubborn snow, whiproot, and campion. Tough grasses grew in clumps inside soft earth, collapsing beneath heavy-soled boots. I find such a sense of belonging in this barren and beautiful landscape. On this ancient earth that carried my father’s boots too.

A journal entry from my father’s caretaker journal at Naylor Lake, dated June 1, 1977. He was 22. Arrive 10:45 am to Naylor lake road junction. Road is still moderately drifted over with snow. Too much snow for driving with four wheel drive. Will be at least two weeks of hot weather before snow is melted enough to drive the 1¼ miles to the lake.

Loaded my backpack with groceries and clothes and hiked in. After unloading my pack I opened the porch shutters and porch door. Also kitchen window and door.

Sandwich and orange for lunch, then it was back to the car for another load. On the way back to the car I saw two women backpacking up. Hope they are properly outfitted for a cold and snowy night. I brought up another load, heavier than the first, and got back to the cabin by 3:30 pm.

I am beginning to stiffen up some now, and notice a slight twinge in my right knee (old backpacking injury).

Cut some kindling for the wood stove and checked the other cabins for any sign of vandalism.

Weather today has been heavy overcast. Can’t even see the tops of surrounding ridges. Temperature this morning was near 55 degrees but by 4:00 pm it was dropping quickly (40 degrees).

Gonna fix some chili on the wood stove, dry and waterproof my boots, smear .on some Bengay, then hit the sack.

I never thought I’d feel this pull to climb mountains. It was never present before February 2014 when my father died.

When a beloved dies, we feel that same pull to gather memories, important possessions, notes, and nostalgia to tether oneself to the lost. It is, I believe, that same pull, the physicality of desire, to climb mountains because my father did.

Because I yearn for him to be by my side.

Because he would have been proud of me.

At the summit, Anthony called his father in Ohio, turning his phone around so that he could see the surrounding peaks, some with lingering snow.

There is often a hot, deep, ache in my chest. There was, that early afternoon, for the opportunity to call my dad from a sun-drenched, airy summit ridge.

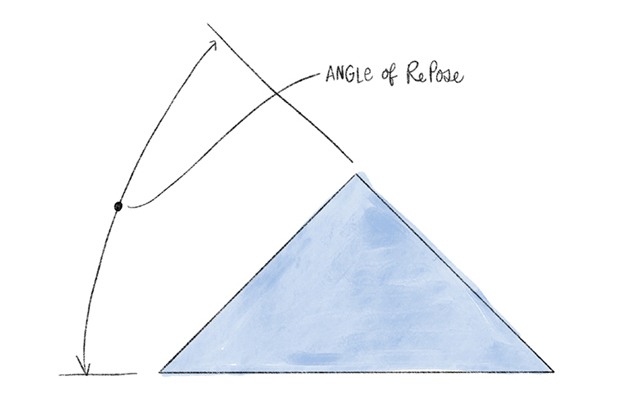

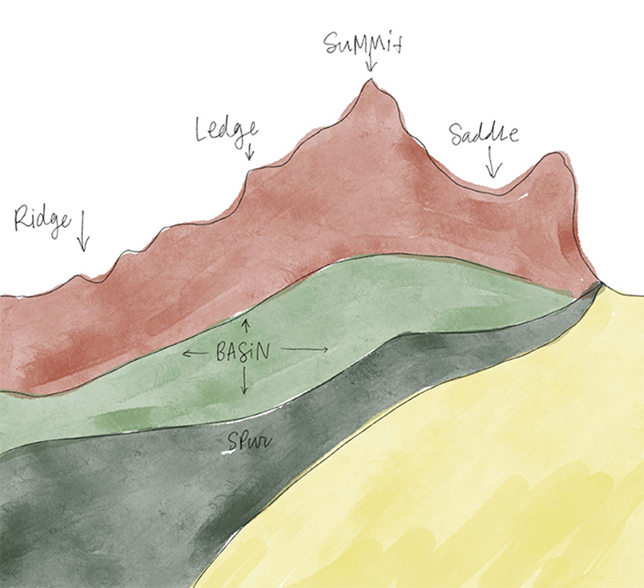

The proud and elongated summit ridge of Mt Yale in the Sawatch Range of the Rockies stretches along the horizon for a half-mile. Talus the size of microwaves pile atop one another until the angle of repose sends the granite toppling down into the parakeet-green valley below. The angle of repose is the steepest angle at which a sloping surface formed of a particular loose material is stable.

I often question what my own angle of repose will be before the memories of him, the sound of his voice, the way he opened the front door after returning home from work start tumbling off the ridge into the valley of other lost memories and moments.

The angle of repose is different for snow than it is for talus. With snow, it can be dangerous because it’s the point at which the snow may start sliding, potentially triggering an avalanche.

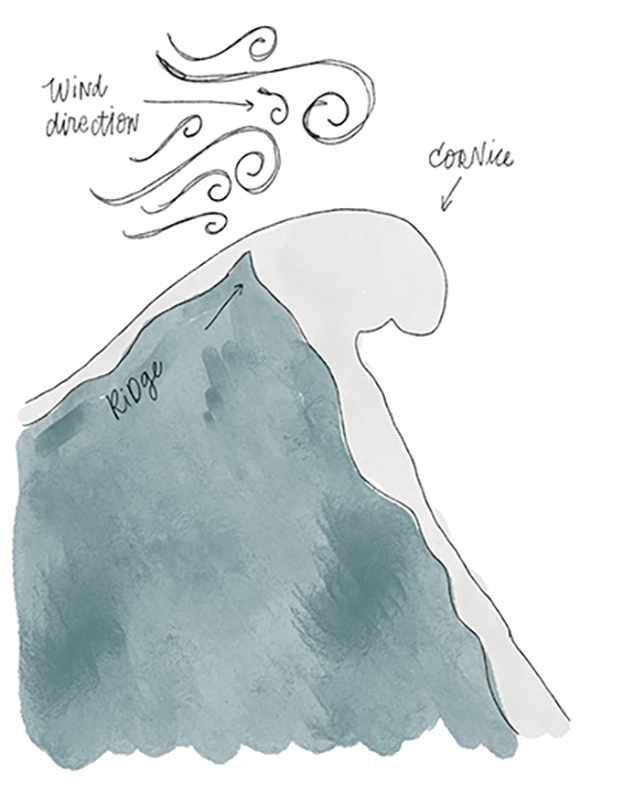

Not always, though, does snow lie patiently in flutes and slopes, resting along the mountainside. Sometimes the high, relentless winds of higher elevations will create a meringued cornice on ridges or terrain breaks.

A cornice, coming from the Italian word meaning ledge, is an overhanging edge of snow on a mountain ridge. A cornice is an illusion of safety and solidity.

Winds blow snow up and over the crest of a mountain, building out horizontally with nothing but air below. It is in that illusion of knowing that part of that pull, a tug towards knowing and experiencing that which doesn’t want to be known and illuminating a truth.

Which I suppose is the same reason I choose to write about mourning.

Grief and cornices are a matter of perspective as so much of mourning and mountaineering are.

An alpinist will often not know that she is atop a cornice until the crack and tumble of the snowy illusion has already happened.

A mourner will often not know that she is atop the cracking ledge of grief until the crack and tumble of the illusion of normalcy and happiness has already tumbled down.

A mountain can look entirely different based on the perspective you have of it. It may look ominous and unattainable from an alpine valley.

A mountaineer may do hard physical work, tundraneering up a steep slope with an eye trained on the highest point, only to realise they’ve only reached a false summit. A false summit appears to be the pinnacle of a peak, but it’s only when an alpinist has crested that pinnacle do they realise they have further to go.

There are at least four false summits on Square Top, depending on how you approach it. Out of shape, not accustomed to the thin air, and totally naïve in terms of what to expect, the false summits had a huge psychological effect on me. I kept staring at them as I leaned on my trekking poles, counting my steps. ‘Fifty steps and then you can take a break’, I’d convince myself.

I’d crest what I thought was the summit and realise that there was more — what felt like a lot more — to go. Normally, I think I’d have gathered up my pride and turned around; clouds were rolling in and there was still no sight of the real summit. But this place was special, I went there to be close to my dad, to be in a place that he had a real reverence for. I think what kept tugging me up that day was knowing how proud he would have been if I’d called him from the summit, looking down on Naylor Lake, at the cabin he spent solitary months in.