Charles Bukowski called poetry ‘what happens when nothing else can’. But what happens when poetry can’t? Through autoethnography and poetic inquiry, this article considers visual writing and alogia, which in psychiatric discourses represents paucity of speech and language indicative of thought disorder. I write as a poet who experiences mild alogia during bipolar depressive phases. While generally manageable, depression for me often forecloses my usual word-based writing practices. Visual poetry, however, remains possible; it becomes the poetry that ‘nothing’ (depression’s void) makes happen. Connecting this phenomenon with research into writing-as-thinking, where poetry facilitates various specialist thought practices, alogia and related negative psychiatric symptoms feasibly reflect thought processes exceeding word-based communication. Such ‘disordered’ thinking may thus be recognised as activating what Keats termed negative capability: poetic reaching through uncertainty towards the un/thinkable (the not-yet-thought, but thinkable). My article supports this argument through analysis of my own and other writers’ visual poems.

Keywords: visual poetry; assemblage; agencement; negative capability; writing as thinking; the un/thinkable

beyond words…

What I remember: the lightbulb blew, seconds after he hung up, me mid-sentence. A coincidence. But Fuck. What a coincidence. I remember shaking. My body shaking. Was I shaking? I wasn’t in my body. Because. I was out of my mind. Where was I? I don’t know. Maybe I was dead. Temporarily. Gone. I wasn’t me. It couldn’t be my life. That body, shaking, was somebody else’s. That somebody’s hands found a pen. Paper. They were writing. No. Scrawling. Screaming. With ink. Pressing hard. Tearing holes. In silence. No sentences. No lines. Nothing nameable as grammar. The words raced up, down, left, right, in circles, spirals and sharp-angled turns. Words scratched over words amid zig-zagging scribbles, exclamations, shapes. A mind-map of blasted terrains, lost bearings. The body of the somebody scrawled, scrawled, scrawled. They shook. They sobbed: breathy, pathetic sobs both animal and beyond-animal. Until—

The memory shared above depicts a turning point: my first experience of being overcome, at sixteen, by poetry that ‘happens when nothing else can’, as Charles Bukowski phrased it (in Orphan 2020) — a poetry of nothingness. This article discusses, first, how poetry of nothingness can transform poets by evoking something like that which John Keats termed ‘negative capability’: poetic reaching through uncertainty towards the un/thinkable (the not-yet-thought, but thinkable) (Keats in Simpson & French 2006). Poetry of nothingness can thereby paradoxically facilitate knowledge-making that helps poets activate previously foreclosed possibilities of agency: considered choice about actions to take and resist. I depict being-written as transformative ‘becoming’ (Zourabichvili 2003: 29-31) via which a poet shifts beyond believing nothing can happen, towards recognition of how to make things happen once more.

To illustrate the above, I discuss how my first experience of writing in response to traumatic news showed me poetry’s problem-solving capacities, leading me to incorporate writing among the suite of non-psychotropic therapies I use to manage my diagnosed mental health condition (bipolar). That writing can benefit mental health is argued across mainstream as well as ‘anti-’ psychiatric literatures (Laing 1967; 1969; Esterling et al 1999; Krpan et al 2013; Winston, Mogrelia & Maher 2016). However, in cases of bipolar and schizophrenia, among other conditions, a complicating factor is that acute phases (e.g. mania, depression, and psychosis) frequently alter language processing, affecting both speech and writing. Mainstream psychiatry deems these changes symptomatic of ‘formal thought disorder’ (Trepacz & Baker 1993: 114; Docherty, Berenbaum & Kerns 2011: 1352).

Although the pathological implications of the word disorder disappoint me, I find the literature around formal thought disorder fascinating, since poetry uses many similar devices. That poetry can be ‘good for thinking’ (Webb 2010) thus enables re-thinking of disorder as this-order — a different mode of thinking neither superior nor inferior to the dominant ones, but instead complementary and capable of raising perspectives and possibilities not easily imaginable in other ways. As Judith Butler in her earlier writings noted, ‘neither grammar nor style are politically neutral’, implying that alternative modes of language can open alternative ways to live, think, be and become (1999: xviii).

A second, trickier problem is alogia — ‘poverty of speech’ (Trepacz & Baker 1993: 117) or ‘decreased verbal productivity, increased latency of verbal response, and decreased syntactic complexity’ (Docherty, Berenbaum & Kerns 2011: 1352). Alongside ‘amotivation, apathy, [and] avolition’, alogia is considered a ‘negative’ mental health symptom, as opposed to ‘positive’ symptoms including ‘delusions, hallucinations, and disorganized behavior’ (Strous et al 2009: 585; see also Toomey et al 1998: 470; Miyoshi 2001: 279; Rossell 2005: 135). Mainstream psychiatrists typically assume alogia indicates ‘diminished mental activity’, and ‘retardation in thinking’ (Miyoshi 2001: 279), but I argue for alogia’s positive re-conception as knowledge-making via negative capability. Towards re-conceiving alogia, I survey writers’ accounts of linguistic challenges accompanying physical illness, depression, trauma, and melancholia. Although these situations differ from one another, and from bipolar (which differs for every individual, as do all diagnosed conditions), common to the accounts I consider is that positive possibilities arise in situations of loss and im/possibility. The other writers’ accounts foreground my description of experiencing mild alogia during bipolar lows, and turning to collage-based visual poetry at such times.

Throughout the article, I intersperse my visual poems with personal reflections, combining poetic inquiry (Prendergast, Leggo & Sameshima 2009) with autoethnography (Rambo & Ellis 2021) to sustain creatively-critical explorations. Recognising everybody’s situation as different, I avoid pitching my personal realisations as “findings”. Rather, I suggest that my coming-to-realisation process reflects alogia as involving cognition beyond words.

on being… written

As earlier noted, Bukowski claimed that poetry ‘happens when nothing else can’ (in Orphan 2020). A similar suggestion is that there are some poems we write, and some that write us — poems of being-written. Being-written happens intuitively, bodily, and affectively. It feels beyond control and incomprehensible in terms of conscious meaning or intent, like the ‘spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings’ William Wordsworth described (Wordsworth and Coleridge 1976: 22).

Crucially, the ‘spontaneous overflow’ becomes poetry when ‘recollected in tranquillity’ (Wordsworth and Coleridge 1976: 42). As contemporary creative writer Kathryn Hamilton Warren notes, ‘it isn’t just sensitivity that’s required, but thought, the ability to connect feelings to subjects that matter’ in ways that, if pursued ‘deliberately and repeatedly’ can generate ‘new “habits of mind”’ (2021: n.p.). The mental transformation Hamilton Warren signals connects with poetry’s ‘negative capabilities’: capabilities for exploring possibilities at the fringes of thought, and expanding these fringes to progressively know more than before (Keats in Simpson & French 2006). For psychoanalytic theorist William Bion, negative capability arouses ‘patience and the ability to tolerate frustration and anxiety’ so as to ‘think in the present moment, even in the face of uncertainty’ (in Simpson & French 2006: 245).

The notion of poetry’s negative capabilities also resonates with arguments from creative writing researchers for poetry as a means of knowledge-generation (Webb 2010; Gibbons 2015), including Grant Caldwell’s (2018) work on un/intention and Dominique Hecq’s (2015) on ‘deferred action’ (nachträglichkeit). Hecq and Caldwell separately observe that poetic composition processes are frequently mysterious to poets. One frequently doesn’t know what one is doing until afterwards (Hecq 2015: 183). ‘Un/intention’ concept describes how poets don’t necessarily know why they write, yet still come to know (more than before) through writing (Caldwell 2018). For Hecq, poetic knowledge-consolidation involves nachträglichkeit: discovery ‘after the fact’ of previously unrecognisable motivations recognised through self-reading, re-reading, revision and/or reflection (Hecq 2015: 8).

To illustrate the above, I return to the memory earlier relayed of my first time succumbing to being-written in response to traumatic news. Previously, I described a disembodied self-detachment — a sense my body and life were no longer mine but that of a beyond-animal somebody else who sobbed and shook as they breathlessly scrawled. What happened next was this:

—they stilled.

The breathing calmed. Some days passed. (How many?) Somewhere in that space, I became me again. No, anew. I found the paper defaced by the panicked body I’d left behind — a testimony of shocks my gone self had failed to bear with. It made no sense. Nonsense. But I made sense of it. With, from, and through it. Extracting words and phrases from the random, odd-angled mess, I structured them into lines, and then the lines into tidy boxes — stanzas: a poem, albeit free-verse and surrealist-influenced, laden thick with symbols, imagery and allusions. Eventually it became two poems, both of which, though juvenile, remain meaningful for me now as then (Walker 2001; 2002).

The second composition phase was, like the first, a being-written, but of a kind different from the first, where being-written meant being driven by forces exceeded my conscious comprehension — that is, by un/intent (Caldwell 2018). In the second phase, nachträglichkeit) was key (Hecq 2015). As earlier noted, I’d received traumatic news and responded instinctively via poetry — initially, a bodily compulsion to scrawl; then, later, a calmer process of transforming my written head-dump into something meaningful for me and shareable with others.

Creating poetic order from poetic chaos, I cognitively processed the traumatic news and consolidated a new sense of self capable of confronting a shifted reality. Writing rewrote my being. I underwent ‘becoming’ — self-transformation (Zourabichvili 2013) — and came to comprehend things I previously couldn’t. Becoming increased my ability to activate agency via considered choices about meanings to make from what had happened and actions to pursue (or refrain from).

poetry, thought, language, affect, and disorder this-order

So far, I have described two phases of poetic composition as being-written through poetry that helped me comprehend things that seemed incomprehensible, and to navigate distressing emotions: the first draft, and revision. The first draft mimicked my world and self: in pieces, chaotic. Reworking it brought order through (re)construction of a new, stronger self. It was survival. It was learning. It got me through.

Writing poetry subsequently became a practice I maintained, and still maintain, for navigating life’s challenges and uncertainties. The knowledges poetry offers are in my view neither superior nor inferior to those of other discourses. But they’re different, because they exceed standard language’s common constraints (Butler 1999: xviii), which enables different, complementary approaches to problems. Paradoxically, poetry often exceeds common language constraints by introducing new ones — for instance, line and syllable counts, and patterns of metre, rhyme, repetition, and more — that provoke innovative solutions to formal problems (Finberg 2015). Not all, or even many of my poems involve dramatic emotional triggers (thank goodness). But the experience awakened me to potentials also accessible in calmer, more deliberate ways through ‘cultivation’ of un/intent using prompts, automatic writing, and aleatory (chance-based) devices (Caldwell & Brophy 2012). Reading and reflecting on other poets’ works also helps (Magee 2009).

At eighteen, I was diagnosed with bipolar. My psychiatrist prescribed lithium, which I initially took believing it best. By twenty, my liver and kidneys were straining. I sought other means. Poetry became incorporated into a suite of non-psychotropic therapies I still engage. I have not had any psychiatric hospitalisations while using these therapies (compared with three within two years medicated). I write to keep track of my cycles, identify triggers, and confront problems that could otherwise undo me. Though I’m wary of certain avenues he pursued, RD Laing’s ‘anti-psychiatry’ informs my approach to so-called mental illness states as meaningful responses to crises of a person’s milieu, including socio-political problems (Laing 1967; 1969). For Laing, poetry provided strategies for working with, rather than against, ‘breakdown’ towards ‘breakthrough’ (1967: 10), which reflects how writing a poem, for me, often involves pressing deeper into some hurt or dilemma to better understand it and the possible responses.

Mainstream psychiatric research similarly touts writing’s wellbeing benefits (Esterling et al 1999; Krpan et al 2013; Winston, Mogrelia & Maher 2016). But where bipolar, schizophrenia, and a number of other conditions are concerned, the use of writing as therapy raises two significant challenges. The first, which I shall address within this section, is formal thought disorder. The second is alogia, to which I will later return.

Formal thought disorder indicates ‘disturbance of the structure or form of thought as opposed to a disorder of thought content’ (Trepacz & Baker 1993: 114) identified via ‘difficult to understand’ or ‘disorganized’ speech (Docherty, Berenbaum & Kerns 2011: 1352) and sometimes writing (Strous et al 2009: 585). Formal thought disorder problematises writing’s therapeutic potentials because poetic devices of rhyme, repetition, and general sense-bending frequently veer close to certain linguistic habits via which mainstream western psychiatrists diagnose disordered thought. For example, ‘clang association’ describes punning, rhyming, or other devices via which sound similarity ‘substitutes for logic’ (Shives 2008: 111-112). Clang association’s similarities to poetry are evident in the account literary critic Reginald Gibbons offers in How Poems Think: Gibbons proposes poetic thought is ‘created by’ rhyme, which ‘may give us supplementary meanings and even phantom statements that the poem does not present explicitly’ (Gibbons 2015: 63).

Echolalia — a formal thought disorder symptom involving ‘parrot-like repetition of overheard words or phrases’ (Shives 2008: 112) — is meanwhile recognisable in poetry through intertextual citations, refrains, and other nods to tradition. Another example is ‘flight of ideas’ — ‘skipping from one idea to another’ via ‘fragmentary’ connections established often via ‘chance associations’ (Shives 2008: 112). In poetic contexts, tangential connections generate originality via novel associations of previously unconnected things to cast fresh perspective on both. Incorporation of neologisms in poetry and formal thought disorder is yet another way in which much poetic thought deploys linguistic pathways that psychiatrists pathologise as disordered.

Poetry’s resonances with formal thought disorder could be part of why poetry has historically been segregated from serious thought and language (Austin 1962). Yet, given arguments for poetry’s knowledge-making capacities (Webb 2010; Gibbons 2015; Hecq 2015; Caldwell 2018), I prefer to argue that poetry can offer inroads towards enhanced empathy with and understanding of supposedly disordered elucidations as meaningful and valuable, and that this forms part of poetry’s therapeutic value: poetry may be what happens sometimes for some people when regular language proves insufficient for thoughts and feelings that push the limits of common experience. Reconceived poetically, formal thought disorder might simply mean this-order — a range of bespoke orders or logic systems neither superior nor inferior to the mainstream ones, merely different, able to operate alongside and in dialogue with dominant thought and language use. Thinking in this-order may enrich both collective and individual knowledges about managing problems, surpassing impasses, and breaking through (via) seeming breakdown (Walker 2019).

Obviously, I bear personal investments in the above argument. Appreciating poetry-as-thinking matters to me. Poetry is how I struggle with and through dilemmas where — even if other things can still happen — I need to think beyond the standard, most obvious pathways towards in/conceivable, im/possible ways through.

Hence, it guts me when poetry itself refuses to happen — for instance, when alogia takes hold.

negative space(s): depression, silence, and capacities

If poetry happens when nothing else can, what happens when even poetry can’t? Alogia is among many factors that can compromise or foreclose language. This section considers accounts from writers who have grappled with linguistic blockages relating to physical illness, depression, and trauma, ultimately identifying positives in seemingly negative experiences. Crucial to recall is the distinctness of all these scenarios, which I wish neither to conflate nor reduce, but to articulate — connect — in a dialogue of related-yet-distinct perspectives and learnings.

The distress involved in compromise of language burns in American essayist BK Loren’s account of illness-induced aphasia. Aphasia differs from alogia in that language is not necessarily reduced but re-routed: one intends to write or say one word, but finds oneself producing another. As Loren relays, ‘fish’ might become ‘bagel’, ‘lion’ ‘table’, and ‘pelican’ ‘funicular’, resulting in ‘gibberish’ (Loren 2013: 205). Loren’s aphasia ‘crashed in overnight’, ‘lasted ten years’ and triggered deep depression (206).

That Loren’s aphasia invoked depression mirrors creative writing researcher Elizabeth Pattinson’s account of depression itself interrupting speech and writing. Discussing lived experiences of cyclical low moods, Pattinson links depression with ‘silence of self’ (2014: 1), ‘quieting’ (4), and reduced capacity to write:

My words, normally quick across the page, clot under the skin. The space between the body, the mind, and the page, thickens and scars. The quietness envelops. I turn off my screens ... Depression might, for the purposes of this paper, be conceived as an interruption. A crack in the passage of consciousness: something that breeds hopelessness. Inertia. (Pattinson 2014: 4)

Pattinson’s account connects with trauma theorists’ descriptions of how trauma interrupts memory and language, riddling narratives of trauma with gaps, silences, and uncertainties (Caruth 1995; Atkinson 2014; Alford 2016). Importantly, I here note that the depression Pattinson discusses is, like my lows, closer to what psychiatrists call the ‘endogenous’ kinds — seemingly genetic, as diabetes, asthma, and other physical conditions can be — whereas trauma is better describable as ‘reactive’ to certain events or situations (as Loren’s depression reacted to illness and language loss). Nonetheless, a commonality is of experience that ‘escapes language’ (Alford 2016), for instance, via a complex ‘dilemma that underlies many survivors’ reluctance to translate their experience into speech’ (Caruth 1995: 154).

Punctuated with ‘gaps’ in memory, trauma ‘exceeds simple understanding’ (156) and is associated with ‘disappearance’, ‘loss’, ‘essential incomprehensibility’, ‘affront to understanding’ (154) and double-bind scenarios where ‘[t]o speak is impossible, and not to speak is impossible’ (Schreiber Weitz in Caruth 1995: 154). Creative writing researcher Meera Atkinson similarly observes how trauma renders the one traumatised ‘speechless by delay, by a lack of psychic registration and the seemingly incoherent reverberations of belatedness’ (2014: n.p.). Atkinson here also evokes psychoanalytic theories regarding how shame plays on memory by inhibiting certain recollections. Trauma theorist Cathy Caruth (1995) deploys psychoanalytic theories to conceptualise how trauma affects memory, problematising (re)construction of liveable self-narratives to sustain self-identity. It therefore seems worth briefly contemplating the psychoanalytic concept of ‘melancholia’.

Melancholia indicates sadness driven by inability to mourn some loss because that loss itself is unrecognised or repressed from consciousness (Butler 1997: 173; Muñoz 1999: 57-76; Ahmed 2010: 141). Potentially stemming from un/recognised or un/knowable trauma, but also associated with other forms of grief, loss, rejection and/or disappointment, melancholia inhibits subjects from explaining their feelings, even to themselves (Butler 1997: 173). Melancholia isn’t necessarily personal: like trauma, it can be intergenerational (Atkinson 2014), cultural and/or shared, as in cases of cultural groups impacted by invasion, slavery, oppression, racism and related modes of abuse (Muñoz 1999; Ahmed 2010). Given its suite of possible causes, melancholia is thus relevant to mnemonic and linguistic lacunae of trauma, pain, sadness, depression, low mood, illness, and more.

So far, I have focused on how aphasia, depressive silence of self, traumatic interruption to memory, and melancholia in different ways, reflect connections between language, thought and affect, evident through the challenges of writing in and/or about such experiences. But the key point is that they all ultimately identify positive valences and possibilities for knowledge-making through such challenges.

For Loren, coming back ‘into existence’ through language recuperation brought ‘learning’ and intensified awe for language that shines bright through the award-winning writings she has subsequently produced. Pattinson meanwhile poses that depression ‘might be more productively considered as products of the coursing, flashing, blinking and ever-moving systems of capitalism’ and revisioned as ‘interruption of the everyday, a fissure in the performance of capitalist life’ (2014: 4). Pattinson describes writing through depressive fissures via assemblage — a Deleuzo-Guattarian mode of ‘writing experiences as a collation’ towards ‘a more holistic and reparative approach to understanding non-linear and traumatic experiences of ‘silence’, or departure from the self’ (in Pattinson 2014: 1). Atkinson, although maintaining that trauma ‘can never be fully knowable or theorised’, asserts, ‘even in the face of this impossibility’, that ‘trauma, affect and the body demand voice and require witness’ (2014: n.p.). The late Jose Esteban Muñoz proposed ‘depathologising’ melancholia as something people of colour and/as queer people frequently find ‘necessary’ — ‘an integral part of everyday lives’ that radically ‘helps us (re)construct identity and take our dead with us to the various battles we must wage in their names — and in our name’ (1999: 74).

The positive re-visionings this section has surveyed of linguistic, mneumonic, and related phenomena typically assumed to be ‘negative’ inform the directions this article’s remaining sections pursue towards my main goal: reconsidering alogia in similarly positive terms.

beyond words / into alogia

The previous section considered, via other writers’ accounts, how reduced language can positively enable different ways of writing and knowing. This section relays my experiences of alogia, focusing for now on its challenges in order to foreground the next section, where, inspired by Loren (2013), Pattinson (2014), Atkinson (2014) and Caruth (1995), I discuss how visual poetry frequently becomes, for me, the poetry that happens when even poetry can’t happen.

To frame my account of alogia, I present a disclaimer: I’ve never been diagnosed with alogia — at least, no doctor has ever told me I have it. I’ve recognised it in myself via reading and self-monitoring. It comes and goes together with my lows. It’s mild, never interfering with my work or social function. I just become less outspoken than usual. (But ‘usual’ for me is quite raucous; I suspect many friends and family sigh with relief when I quieten down for a while). I still speak, just not more than needed. I take longer to reply in conversations, and think harder about what to say. These aren’t necessarily bad things. They’re much preferable to when my mouth moves faster than my mind, generating prolific foot-in-mouth scenarios. Other positives are I listen more, demand less, and take more time to reflect on things others say. Aside from becoming somewhat boring, I’m probably a better, more considerate person than in other, more excitable states.

Alogia’s main problem, for me, is writing poetry. Book reviews, articles, emails, and workplace correspondences all remain possible, albeit more slowly, with increased effort. What alogia saps from me is creative wordplay. Sometimes, this doesn’t bother me. All writers have non-writing phases, right? (Some might suggest that I am being melodramatic, applying a fancy label to what could equally be called commonplace creative blockage). Analogous to social situations, I’m sometimes content to just express less and listen more — as in, listening on paper: reading, learning, and reflecting on what other poets write. Sometimes, a low can be pleasant and restful, like drawing breath between one sentence and the next or resting sore muscles during a break between phases of intense physical training. In these cases, speechlessness and silence can bear curious pleasures.

Then, there are other times.

Twentieth-century British playwright Sarah Kane wrote of ‘a night in which everything was revealed to me. / How can I speak again?’ (2001: 205). This perfectly describes the frustrations that swarm during certain low phases when I sense a problem requiring working out through the poetry alogia forecloses. It’s a heavy feeling, a pressure, something undeniably t/here, yet invisible, intangible, inexplicable… Well no. Not inexplicable, rather in/explicable. Potentially explicable, but not via the means I most ordinarily pursue.

This is where visual poetry comes in — where alogia, too, becomes invested with positive valences of negative capacities towards un/knowings.

alogia’s productive constraints, visual poetry, and assemblage/agencement

If poetry happens when nothing else can, visual poetry is what happens, for me, when even poetry can’t — what I write when alogia takes hold. That I do so resonates with mental health research indicating asemic writing — ‘written expression in which the written material has no discernible semantic content; the letters appear to be illegible and are open to varied interpretations’ — frequently appeals to people with alexithymia, a condition involving alogia (Winston et al 2016: 142-144). While my lows differ majorly from alexithymic being, and while my visual poetry practices differ from asemic writing via inclusion of recognisable signifiers (such as maps and music scores), the commonality is that images come in where words fail, affirming a point visual artists know well: visual expression involves cognition exceeding that of word-based languages (Witton et al 2016: 153-154).

That alogia pushes me towards visual poetry reflects how alogia, though assumed negative, can become positive, much as constraint-based poetics unlock un/conscious un/intention: when habitual processes are unavailable, one pursues alternative pathways, exploring possibilities one otherwise probably wouldn’t explore (Finberg 2015). Alogia introduces constraints that force negative capacities. Music, movement, sculpture and a plethora of other media could also provide similarly effective places for poets to go when words won’t come, but for me, visual poetry feels accessible during phases of alogia because I also write it at other times. I foreground, however, that all my forays into visual poetics are playful and exploratory: I lay no claim to critical expertise, and flag the literature around ‘VisPo’ (Vassilakis & Hill 2012) as far exceeding what this article relays.

I began playing with visual poetry following a workshop with Australian poet, performance artist and publisher, ∏O. ∏O’s Numbers Poems (2000) — wordless poems fully based on spatial arrangements of numbers and mathematical symbols — revolutionised my conceptions of what poetry is and can do. Regarding possible questions of how visual poetry differs from visual art, I personally class my work as visual poetry, not art, basically because I have no training or skill in artistic creation, and because my interest is, as with word-based poems, in formal arrangements of symbols and signifiers in unusual ways that provoke new connections and possibilities (although I also recognise that equivalent tendencies are recognisable among artists, and that distinctions might after all be pedantic and redundant).

The visual poetry practices I mostly explore when experiencing alogia are collage-based. Perhaps this is because collage doesn’t require generating original content; in the spirit of the bricoleur, I go to whatever materials are at hand (Aagard 2019). My processes resonate with Pattinson’s ‘writing experiences as a collation or assemblage of practices’ as a means to ‘gain a more holistic and reparative approach to understanding non-linear and traumatic experiences of “silence”, or departure from the self’ (2014: 1). Pattinson deploys the Deleuzo-Guattarian concept of assemblage/agencement. To avoid problematic conflation of Deleuzo-Guattarian assemblage with common senses of intentional artistic acts of assembling disparate parts to form a new whole, I am emphasising the French term, agencement (Zourabichvilo 2003: 6-10). Collage practices, including my own, can entail agencement, but for other reasons; agencement occurs through, and offers thought much more beyond mere combinations of materials (Hanley 2018).

Deleuze and Guattari gave agencement at least ‘half a dozen different definitions’ (Hanley 2018: 4). Hanley treats it as ‘internal dynamic through the co-functioning of parts’ (2018: 2), while Zourabichvilo emphasises two axes and segments: content and expression (2003: 6). Axis one concerns, on one hand, bodies, actions and passions, and on the other, collective acts of enunciation and immaterial transformations attributed to the material. Axis two involves territorialisation and deterritorialisation—territorialising factors being those that control and potentially oppress, and deterritorialising ones being those that undo such controls, seeking liberation and pursuing desires down lines of flight (fuite: fleeing from and running towards, in a taking flight sense) (Zourabichvilo 2003: 6-7). Relevant to visual poetry and alogia, agencement opens potentialities for new knowing, negative capacity, and un/intention. Agencement problematises assumptions about agency: the subject is never fully in control, nor controlled; freedom, choice, and action are always contingent; we are always driven by more than we know, which drives desire for knowing more (Zourabichvilo 2003: 7).

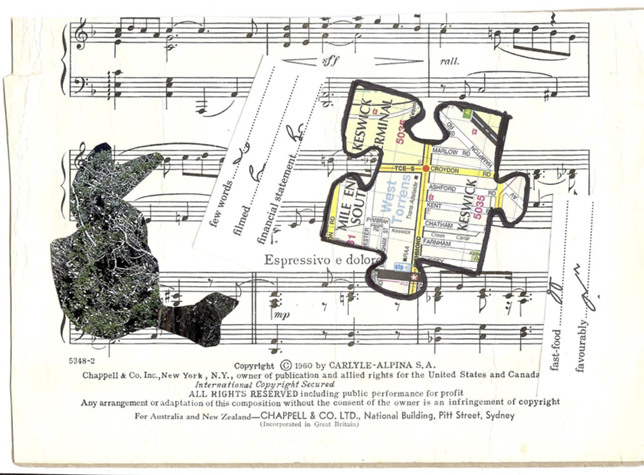

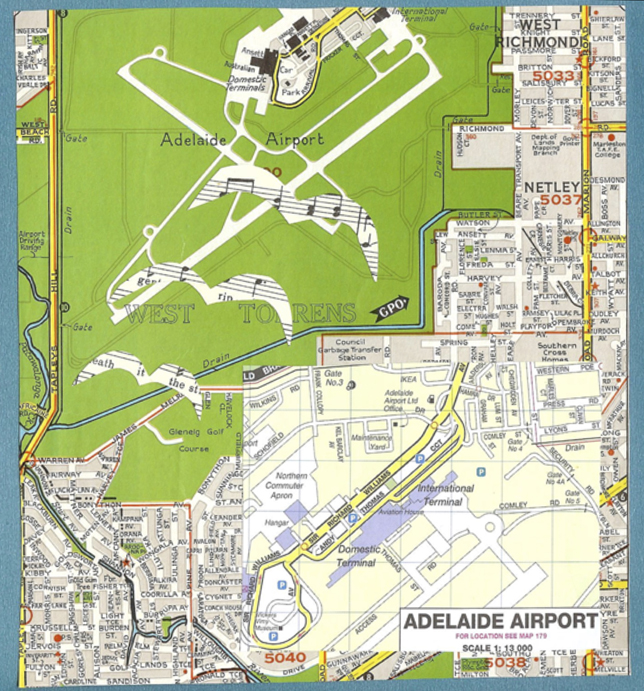

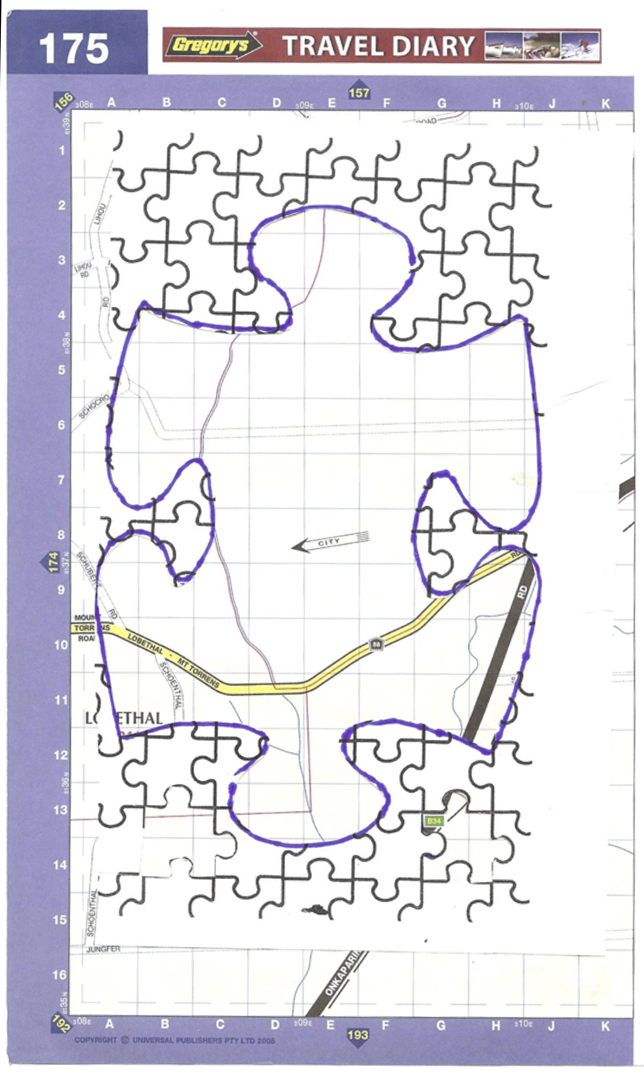

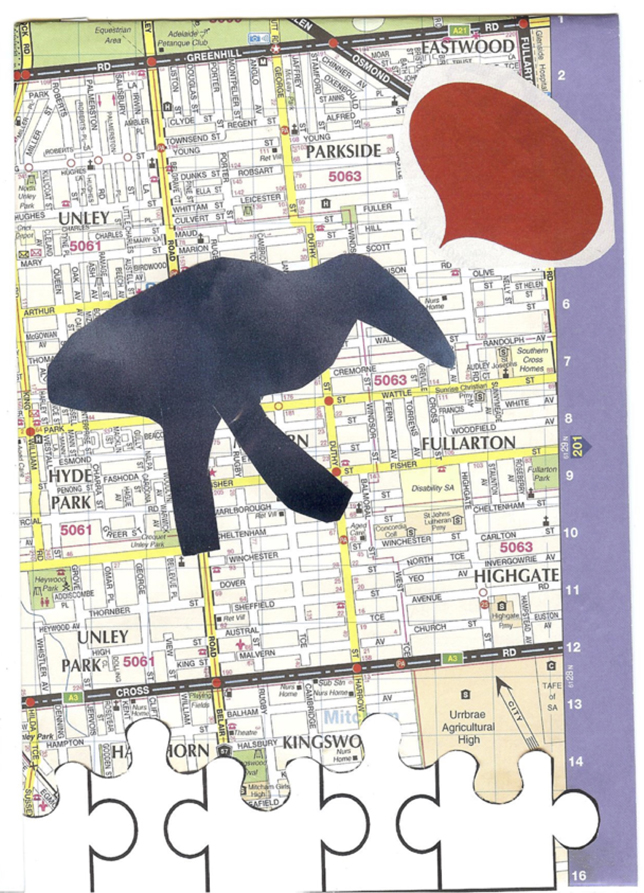

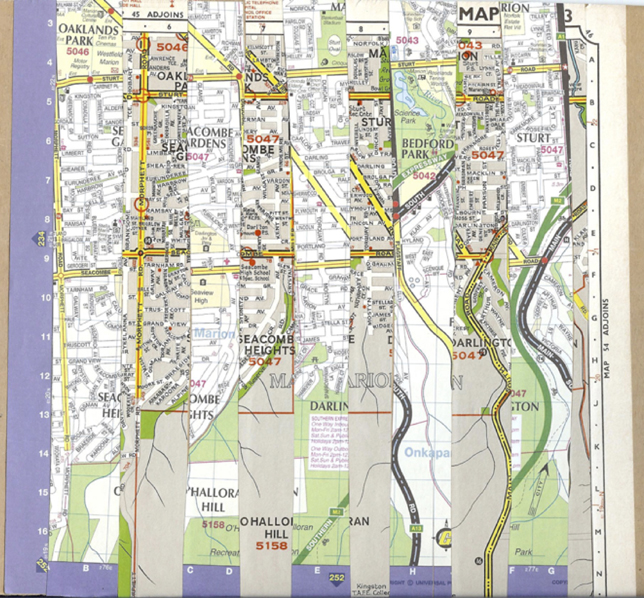

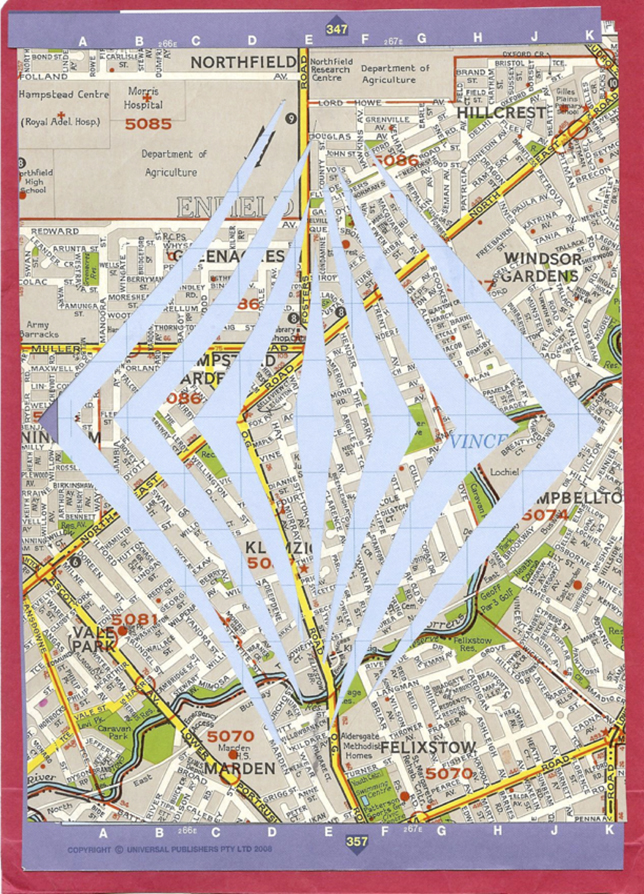

Agencement, by complicating agency, reflects the un/intentional processes my visual poetry involves. It’s messily driven by trial and error, accidents and chance (Finberg 2015). Making visual poetry reminds me of those first poems I wrote, at sixteen, when it seemed my body was no longer mine and that somebody else was writing. Making visual poetry, I rarely think about what I’m doing; things land on paper; later, I return to ask how and why things landed as they did. That’s how Figures One to Seven were created, using out-of-date road maps, teeline shorthand manuals, music scores, national geographics, and a self-help manual. They are part of a series, other pieces from which were published in Unusual Work issue #28 (∏o 2019).

Creating Figures One to Seven, I was guided by un/intent (Caldwell 2018). Reviewing them, nachträglichkeit (Hecq 2015) through self-reading brought me to reconceive them as ecopoems about environmental destruction. While I recognise meaning in poetry to be slippery — an author’s interpretation of meaning bears no privilege over interpretations other readers might produce — the act of self-reading nonetheless helped me consider contemporary ecological problems in ways beyond how I had previously done, thereby expanding my scope for thought and knowing. To illustrate some ecological readings of the poems, Figures One and Seven, juxtaposing water and maps, can be read as allusions to rising tides and climate change. The splicing of old against new maps in Figure Six and blank puzzles in Figure Four conceivably reflect overdevelopment, unsustainable farming, and fast-changing landscapes. Silhouetted birds in Figures Two, Three, and Five are meanwhile interpretable as signifying species extinction — Figure Three with emphasis on air travel’s carbon emissions.

The ecological themes readable in the poems perhaps partially stem from the source materials — texts salvaged from library throw-away piles and hard rubbish. Otherwise destined for landfill, they begged for one last hurrah. My desire to make poems of them reflects an agencement arising through connections between multiple contingent factors, including but exceeding myself and ecopoetry’s existing intersections with visual poetry via ecopoetic use of typeless spaces signifying ecological destruction (Walker 2020). Similar deployments of typeless space are notable in Ava Hoffman’s poetic critique of neoliberal violences, where space activates silence as protest. Hoffman explains:

My writing process operates primarily through the creation of textual rot–fragments, lacunae, and revisions — and through this incompleteness directly interact with the reader and challenge them when it comes to queerness/transness, our neoliberal-capitalist moment, and the yawning void of history (Hoffman 2019: n.p.).

Hoffman’s account helps me recognise speechlessness — alogia — speaking itself through the visual poems I made while in alogia’s negative space (of potentialities). In Figure Two, the music symbol trailing from the bird’s mouth to the teeline shorthand for ‘few words’ can simultaneously suggest speech and vomiting — emesis symbolising ineffable disgust at ‘fast food’, ‘financial statements’, and the ecological recklessness of capitalist greed. The red speech bubble in Figure Six may similarly be read as evoking love, emergencies, danger and/or mourning im/possible communication with beyond-human beings whose utterances I would like to understand, but can’t. I here note Tom Hawkins’s depiction of animal narrators in classic Greek literature as figures of ‘eloquent alogia’ (2017: 37) and Mark Roper’s case for reconsidering anthropocentric assumptions that animals don’t speak: evidence exists that animals communicate with one another, and that animal languages influenced human language development; in earlier times, we learned from our co-species, and we could yet open ourselves to such learning towards possibilities of inter-species mutual aid (Roper 2020).

opening space/s

This essay’s objective has been to reconceive alogia in positive terms. I have pursued my objective by describing how review of visual poems produced while experiencing alogia helped me articulate previously un/known knowledges. Importantly, the knowledges I constructed through self-reading were not intended as research ‘findings’ or recommendations to inform others. Everybody’s experience is different. My aim has been to demonstrate how, by producing visual poems in a state of alogia and later re-reading them, I was able to activate poetry’s negative capabilities for broaching the un/thinkable and thereby coming to know more than before. By describing my coming-to-know process, I have sought to illustrate that alogia does not necessarily indicate lack of thought, but can in some instances facilitate thinking that exceeds and complements the insights both standard and non-standard modes of language offer.

Aagard, M 2009 ‘Bricolage: making do with what is at hand’, Creative Nursing 15 (2), 82-4

Ahmed, S 2010 The Promise of Happiness, North Carolina: Duke University Press

Alford, CF 2016 ‘Trauma escapes language, but so does life’, About Trauma, 12 July, at https://traumatheory.com/trauma-escapes-language/#more-601 (accessed 2 July 2021)

Atkinson, M 2014 ‘Strange body bedfellows: Écriture féminine and the poetics of trans-trauma’, TEXT: Journal of Writing and Writing Courses 18:1, at http://textjournal.com.au/april14/atkinson.htm (accessed 2 July 2021)

Austin, JL 1962 [1975] How to Do Things With Words, 2nd Edition, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

Butler, J 1997 The Psychic Life of Power, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press

Butler, J 1999 Gender Trouble (Tenth Anniversary Edition), New York, NY: Routledge

Caldwell, G & Brophy, K 2012 ‘The poet-paradox: A model of the psychological moment of composition in lyric poetry’, TEXT: Journal of Writing and Writing Courses 16:2, at

http://www.textjournal.com.au/oct12/caldwell_brophy.htm (accessed 2 July 2021)

Caldwell, G 2018 Intention and Unintention or the Hyperconscious in Contemporary Lyric Impulse, North Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing

Caruth, C 1995 Trauma: Explorations in Memory, Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press

Cohen, AS, Mitchell, KR, & Elvevåg, B 2014 ‘What do we really know about blunted vocal affect and alogia? A meta-analysis of objective assessments’, Schizophrenia Research 159 (2-3), 533-8

Docherty, AR, Berenbaum, H, & Kerns, JG 2011 ‘Alogia and formal thought disorder: Differential patterns of verbal fluency task performance’, Journal of Psychiatric Research 45 (10), 1352-1357

Esterling, BA, L’Abate, L Murray, EJ, & Pennebaker, JW 1999 ‘Empirical Foundations for Writing in Prevention and Psychotherapy: Mental and Physical Health Outcomes’, Clinical Psychology Review 19 (1), 79–96

Finberg, KC 2015 ‘Toward an embodied critique: A review of Louis Bury's Exercises in Criticism’, Jacket2, 20 October, at https://jacket2.org/reviews/toward-embodied-critique (accessed 2 July 2021)

Gandolfo, E 2014 ‘Take a walk in their shoes: Empathy and emotion in the writing process’, TEXT: Journal of Writing and Writing Courses 18:1, at https://www.textjournal.com.au/april14/gandolfo.htm (accessed 2 July 2021)

Gibbons, R 2015 How Poems Think, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press

Hamilton Warren, K 2021 ‘Wordsworth and the Paradox of Self-Writing: Defending the journey inward’, The Hedgehog Review: Critical Reflections on Contemporary Culture 10 June,

https://hedgehogreview.com/web-features/thr/posts/wordsworth-and-the-paradox-of-self-writing

(accessed 2 July 2021)

Hanley, C 2018 ‘Thinking with Deleuze and Guattari: An exploration of writing as assemblage’, Educational Philosophy and Theory 51 (4), 413-423

Hawkins, T 2017 ‘Eloquent Alogia: Animal Narrators in Ancient Greek Literature’, Humanities 6 (2), 37-52

Hecq, D 2015 Towards a Poetics of Creative Writing, Bristol: Multilingual Matters

Hoffman, A 2019 ‘Four Poems’, BOMB-CYCLONE 3: July, http://www.bomb-cyclone.com/issue-three/ (accessed 2 July 2021)

Kane, S 2001 Complete Plays: Blasted; Phaedra's Love; Cleansed; Crave; 4.48 Psychosis; Skin, London: Methuen

Krpan, KN, Kross E, Berman, MG, Deldin, PJ, Askren, MK, & Jonides, J 2013 ‘An everyday activity as a treatment for depression: The benefits of expressive writing for people diagnosed with major depressive disorder’, Journal of Affective Disorders 150 (3), 1148-51

Laing, RD 1967 The Politics of Experience and the Bird of Paradise, Harmondsworth: Penguin

Laing, RD 1969 The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness, Harmondsworth: Penguin

Loren, BK 2013 Animal Mineral Radical: essays on wildlife, family and food, Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint

Magee, P 2009 ‘Is Poetry Research?’, TEXT: Journal of Writing and Writing Courses 13 (2), at https://www.textjournal.com.au/oct09/magee.htm

Miyoshi, K 2001 ‘Depression Associated with Physical Illness’, Japan Medical Association Journal 44 (6), 279–282

Muñoz, JE 1999 Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press

Orphan, K 2020 ‘A Condition Not a Profession: “Poetry is what happens when nothing else can”’, Kenn Orphan, 10 October, at https://kennorphan.com/2020/10/10/a-condition-not-a-profession-poetry-is-what-happens-when-nothing-else-can/

Pattinson, D 2014-2015 ‘Writing Across the Fault lines of Depression: Towards a Methodology of Writing the Silences of Self’, Minding The Gap: Writing Across Thresholds and Fault Lines: The Refereed Proceedings of the 19th Conference of The Australasian Association of Writing Programs, 2014, Wellington NZ, at https://www.aawp.org.au/publications/minding-the-gap-writing-across-thresholds-and-fault-lines/

Prendergast, M, Leggo, C & Sameshima, P 2009, Poetic Inquiry: Vibrant Voices in the Social Sciences, Leiden: Brill

∏o 2000, Number Poems, Fitzroy: Collective Effort Press

∏o (ed.) 2019 Unusual Work 28, Fitzroy: Collective Effort Press

Rambo, C, & Ellis, C 2021 ‘Autoethnography’ in G Ritzer (ed.), The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology, at https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405165518.wbeosa082.pub2 (accessed 22 July 2021)

Roper, M 2020 ‘The Loneliness’, AXON: Creative Explorations 10 (2), at

https://www.axonjournal.com.au/issue-vol-10-no-2-dec-2020/loneliness (accessed 22 July 2021)

Rossell, SL 2005 ‘Category fluency performance in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: The influence of affective categories’, Schizophrenia Research 82 (2-3), 135-138

Shives, LR 2008 Basic Concepts of Psychiatric-mental Health Nursing, Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Simpson, P, & French, R 2006 ‘Negative Capability and the Capacity to Think in the Present Moment: Some Implications for Leadership Practice’, Leadership, 2 (2), 245–255

Strous, RD, Koppel, M, Fine, J Nachliel, S, Shaked, G, & Zivotofsky, AZ 2009 ‘Automated Characterization and Identification of Schizophrenia in Writing’, The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 197 (8), 585-588

Toomey, R, Faraone, S, Simpson, J, & Tsuang, M 1998 ‘Negative, Positive, and Disorganized Symptom Dimensions in Schizophrenia, Major Depression, and Bipolar Disorder’, The Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease 186 (8), 470-476

Trzepacz, PT, & Baker, RW 1993 The Psychiatric Mental Status Examination, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Vassilakis, N & Hill, C 2012 The Last Vispo Anthology: Visual Poetry 1998-2008, Seattle, WA: Fantagraphics Books

Walker, A 2001 ‘Stars/(Don't Blame Marx)’, Sidewalk 7/8, 130

Walker, A 2002 ‘Ophelia's Overdose’, Sidewalk 10, 80

Walker, A 2019 ‘This order, not disorder: break down as break through’, in AM McCulloch & RA Goodrich (eds) Why Do Things Break?, Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing

Webb, J 2020 ‘“Good to think with”: words, knowing and doing’, Strange Bedfellows or Perfect Partners: The Refereed Proceedings of the 15th Conference of The Australasian Association of Writing Programs, at https://www.aawp.org.au/publications/the-strange-bedfellows-or-perfect-partners-papers/ (accessed 22 July 2021)

Winston, CN, Mogrelia, N, & Maher, H 2016 ‘The Therapeutic Value of Asemic Writing: A Qualitative Exploration’, Journal of Creativity in Mental Health 11 (2), 142-156

Wordsworth, W and Coleridge, ST 1976 [1805] Lyrical Ballads, ed. D Roper, London: MacDonald and Evans

Zourabichvili, F 2003 Le vocabulaire de Deleuze, Paris: Ellipses